A ne’er-do-well exploits his gentle daughter’s beauty for social advancement in this masterpiece of tragic fiction. Hardy’s 1891 novel defied convention to focus on the rural lower class for a frank treatment of sexuality and religion. Then and now, his sympathetic portrait of a victim of Victorian hypocrisy offers compelling reading.

Tess of the D’Ubervilles by Thomas Hardy

Tess of the D’Ubervilles by Thomas Hardy

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I think I first heard about this book as a young person, and for some reason, I always thought about this book in a negative light. I was not even aware that it was a classic book from the late 1800’s. I also had only heard of Thomas Hardy and was mildly aware of his being a British author.

I remember seeing a blog discussion of this book, and I thought it was high time I read it. I was certain I would like it, but I had no idea just how much I would!

From the start, I was absolutely enthralled with Hardy’s command of the English language. I always thought Dickens was descriptive in his books, but Hardy is just as good without being dry or dull. I always used to say that most classics (Dickens, Twain, and the like) took about 50 pages before they really got going. This book captured my attention from the very first page.

In addition to this, I must commend Hardy for painting an intricate (and accurate) portrait of a woman. I do not believe many male authors are able to capture the true spirit of a woman–especially men of this time period. Most women in classic novels are two-dimensional at best unless written by a woman. Not so with Hardy. He captured the heart of Tess in such a way that as I neared the end, I feared for the inevitable to occur. But in all this, Tess never ceased to be a strong woman of the soil who would do whatever she must.

I can only guess that any negativism I sensed concerning this book as a child would be due to some very adult topics within the novel. I will say that Hardy handled the issues with delicacy and decorum, but the book is certainly not intended for the naive and ingenues of the reading community.

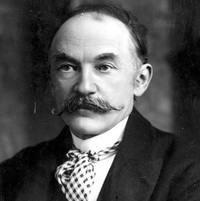

Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy

The Dorset countryside near Cheddington |

|

Did You Know?

|

|

A rumour has persisted since Hardy’s death that it is not the author’s heart that was buried beside Emma. The story goes that Hardy’s housekeeper placed his heart on the kitchen table, where it was promptly devoured by her cat. Apparently a pig’s heart was used to replace Hardy’s own. Truth? Fiction? We will probably never know.

|